Chip in Now to Stand Up for Working People

Working people need a voice more than ever and Working America is making that happen.

Working people need a voice more than ever and Working America is making that happen.

05/24/2018

The loss at the presidential level was the largest swing from Democrat to Republican of any state in the country. When Hawkeye State voters head to the polls this fall, they will signal whether the sharp move to the right was just a one-time fluke or the consolidation of long-term control of state politics by conservatives.

Iowa Republicans secured a coveted trifecta in 2016 when they won the state Senate. Since then, they have used their unified control of government to marshal an all-out attack on progressive policies and those organizations that support them, especially labor unions. They have set to work slashing public services and unraveling the social safety net for thousands of working families. From privatization of the state Medicaid program to closing half the state’s mental hospitals to cuts to public education funding to “backdoor gerrymandering” to retain their control, the state GOP has advanced an extreme conservative agenda in Iowa. These recent right-wing advances give progressives all the more reason to assess the current political environment and use the information to craft a pathway to victory this election cycle. In a polarized landscape, how can progressives take advantage of Blue Wave energy among base voters and make up ground by focusing their outreach on the voters most likely to be persuaded?

To help answer that question, Working America, the community affiliate of the AFL-CIO, conducted a large-scale listening project to understand what’s animating voters in and around Cedar Rapids and in eastern Iowa’s small towns such as Dyersville and Maquoketa. In late March, we held 335 front-porch conversations with liberal and swing voters from working-class neighborhoods, excluding the most hardened conservatives from our targeting to concentrate on understanding movable voters. Our canvassers engaged middle partisans and soft Democrats to assess Iowa’s political landscape, understand the issues that matter to them and determine their economic outlook for their community. We asked them to rate the job performance of Gov. Kim Reynolds as well as Rep. Rod Blum. We also wanted to learn who they see in public life as acting in their best interests as well as their views on health care, cuts to mental health and the proposed tax overhaul bill. Our conversations revealed points of vulnerability as well as opportunities for progressives to reconnect with voters and lift up and champion key issues. If progressives are ambitious about engaging with swing voters this fall, they have an opportunity to win back lost support and shift the balance of power at the state and federal levels.

Working America has been a mobilizing force in Iowa’s cities as well as smaller and more rural communities for more than a decade, with more than 24,000 members across Iowa’s 99 counties. In our latest Front Porch Focus Group report, our findings suggest a path forward for progressive candidates hoping to reclaim votes and begin the process of long-term realignment in the state.

Here’s what we found:

Discussion

Iowan’s economic confidence is lower than in other battleground states.

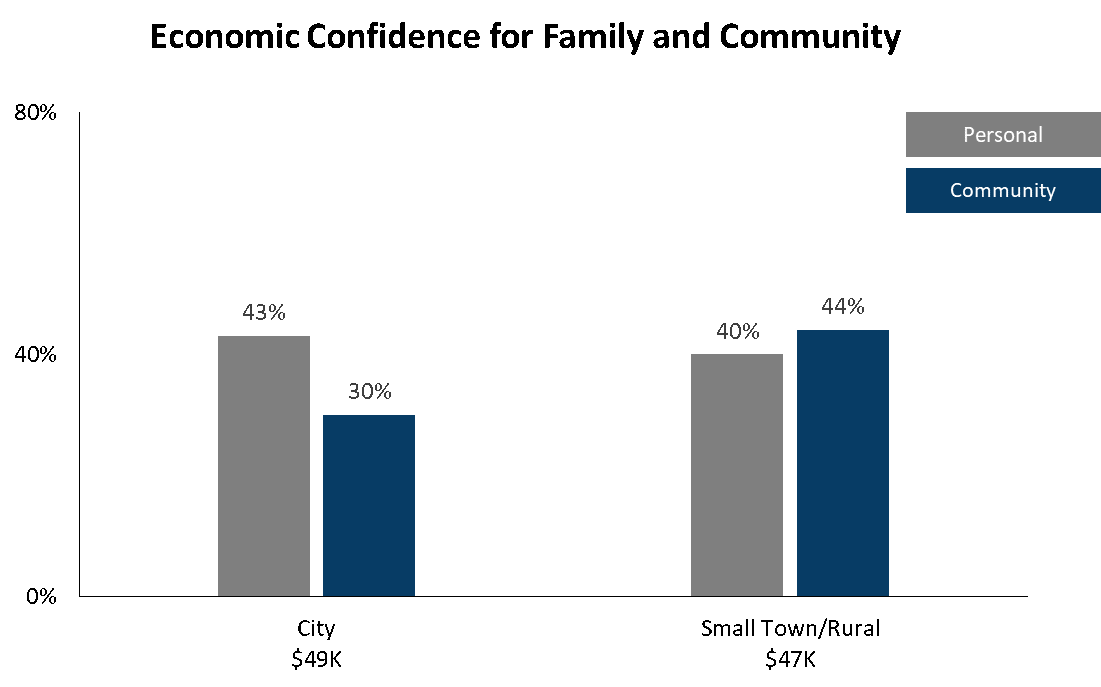

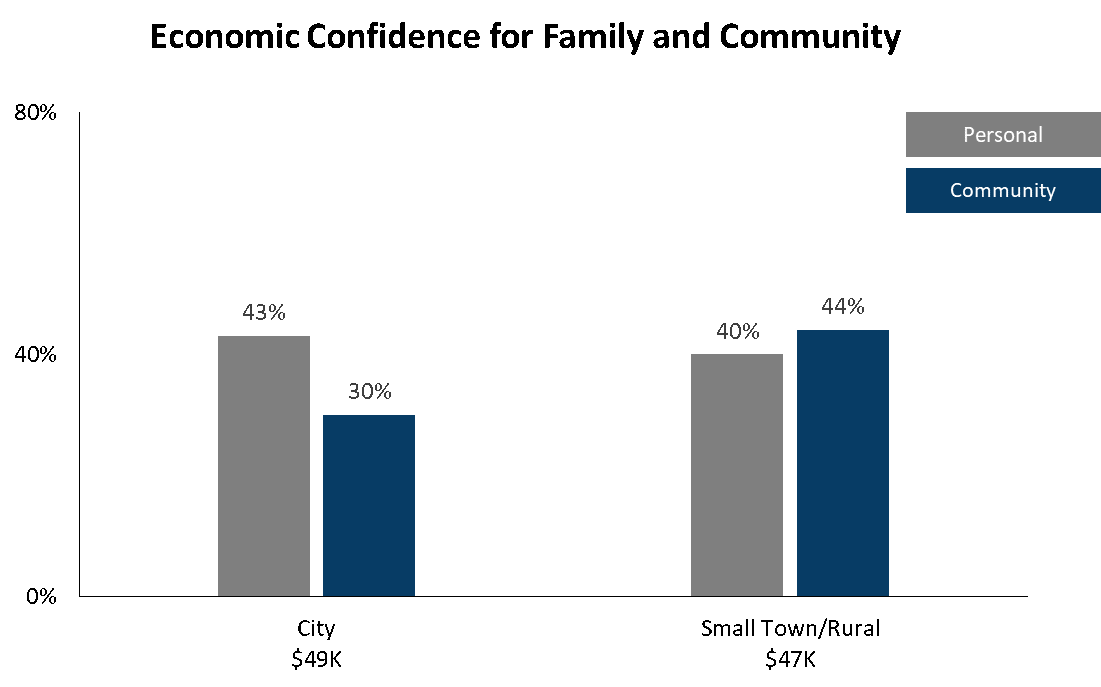

Our canvassers reported a startling lack of economic confidence among the voters they spoke with in eastern Iowa. Time and again, they encountered pessimism about the economic future of the state. When asked to rate whether they felt “confident” or “concerned” about their economic prospects and those of their community, voters expressed concern about where things are headed.

We asked people about the economic changes they’d seen over the past decade. Over a third had seen a negative change in their economic circumstances over the past decade (35 percent). Over 40 percent said they’d seen no change over the last decade, and just 14 percent said their economic circumstances had improved.

We then asked people how confident or concerned they were about the economic future of their families and their community.

While personal economic confidence was nearly identical in both cities and small towns, we found that people living in cities (Cedar Rapids, Dubuque, and Waterloo) were far less confident about their community’s economic future than people living in small towns (Dyersville, Maquoketa, and Oelwein). Just 30 percent of city residents were confident about the community’s economic future, compared to 44 percent of small-town residents.

Jason, a 41-year-old diesel mechanic in Cedar Rapids, is a registered Democrat but voted for Trump. When asked about the community’s economic future, he said, “I think this town is in a downward spiral. They need more things for the youth to do if we’re going to keep people here.”

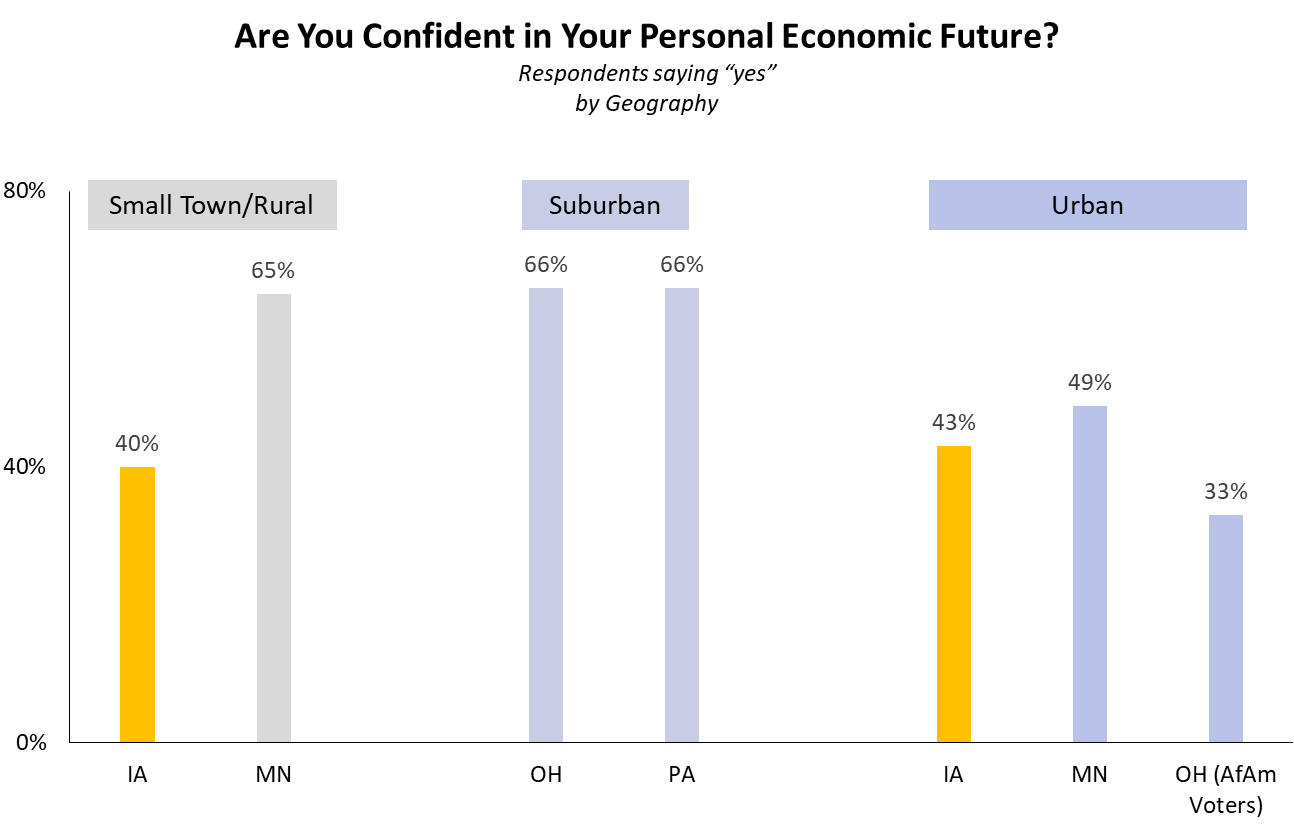

We’ve had thousands of recent conversations with voters in battleground states, including Minnesota, Ohio and Pennsylvania. Compared to these states, Iowa’s low levels of economic confidence stand out.

The chart above shows personal economic confidence across several battleground states. When comparing small towns and rural areas in Iowa and Minnesota, we see that 25 percent fewer Iowans felt confident about their economic future than Minnesotans.

Providing further context, in 2017, we undertook a large-scale listening project among African-American voters in Columbus, Ohio. The economic confidence in small town and rural areas of Iowa is closer to that of the urban African-American population — with mean wages well below the region and higher unemployment than surrounding communities — in Ohio than it is to other predominately white communities with positive economic indicators. These data reveal Iowans are deeply concerned about the economic future of their communities.

Swing voters who supported Donald Trump in 2016 are moving away from him at a faster rate than in other battleground states.

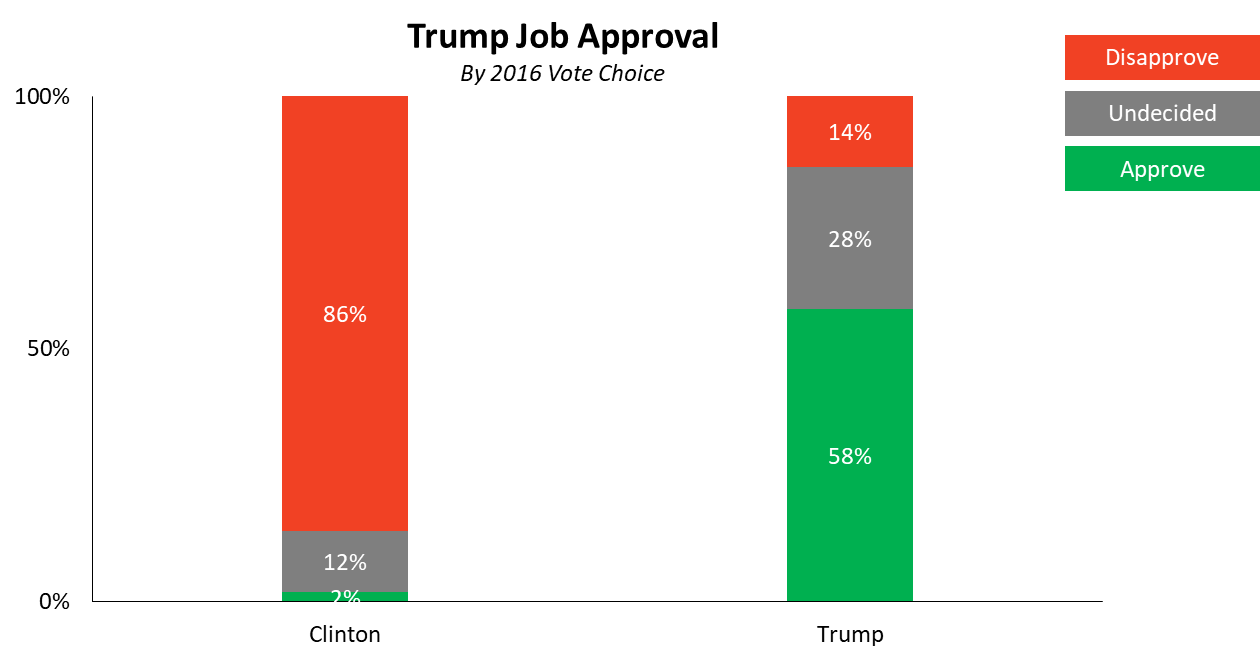

Voters who supported Hillary Clinton in 2016 overwhelmingly disapprove of President Trump’s job performance, while Trump voters generally approve of the president. Fully 86 percent of Clinton voters disapprove of Trump, compared to just 14 percent of Trump voters.

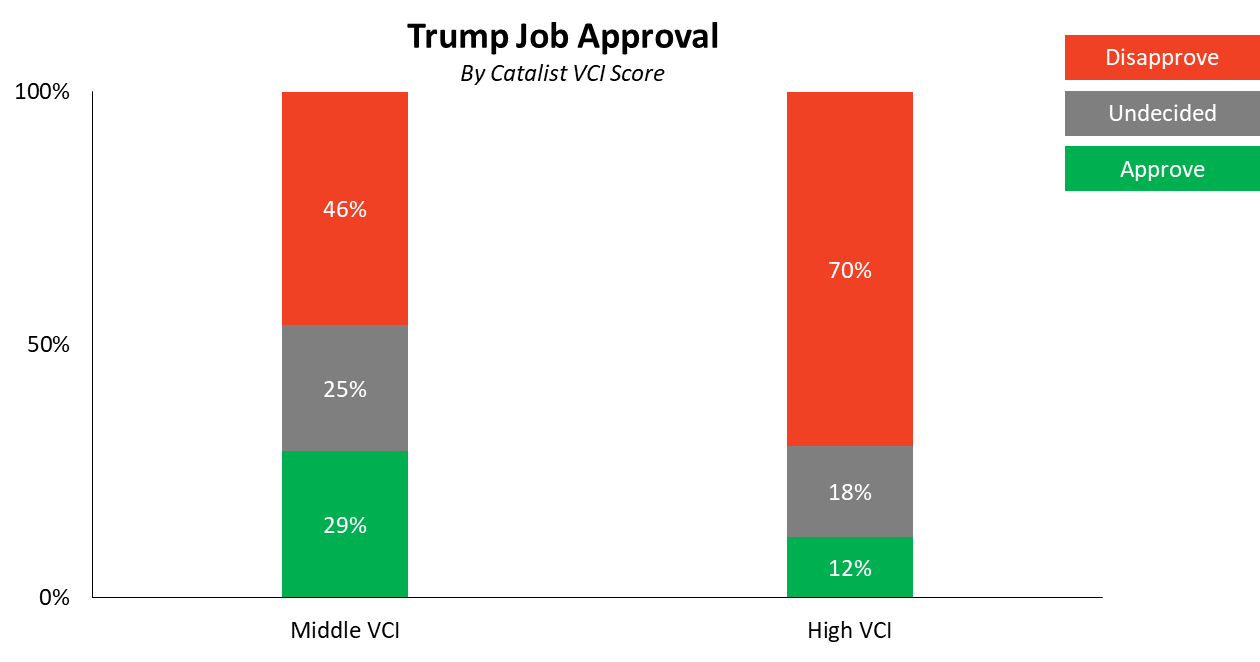

The graph below shows Trump job approval broken down by VCI, or Vote Choice Index. Vote Choice Index is a proprietary measure developed by Catalist. VCI is a scale from 0-100, with higher scores indicating a likelihood to vote for Democrats and lower scores indicating a likelihood to vote for Republicans.

Among high VCI voters, or likely Democratic voters, Trump has a 70 percent disapproval and 12 percent approval. Among middle VCI voters, or swing voters, Trump’s approval stands at 25 percent, while his disapproval is 46 percent.

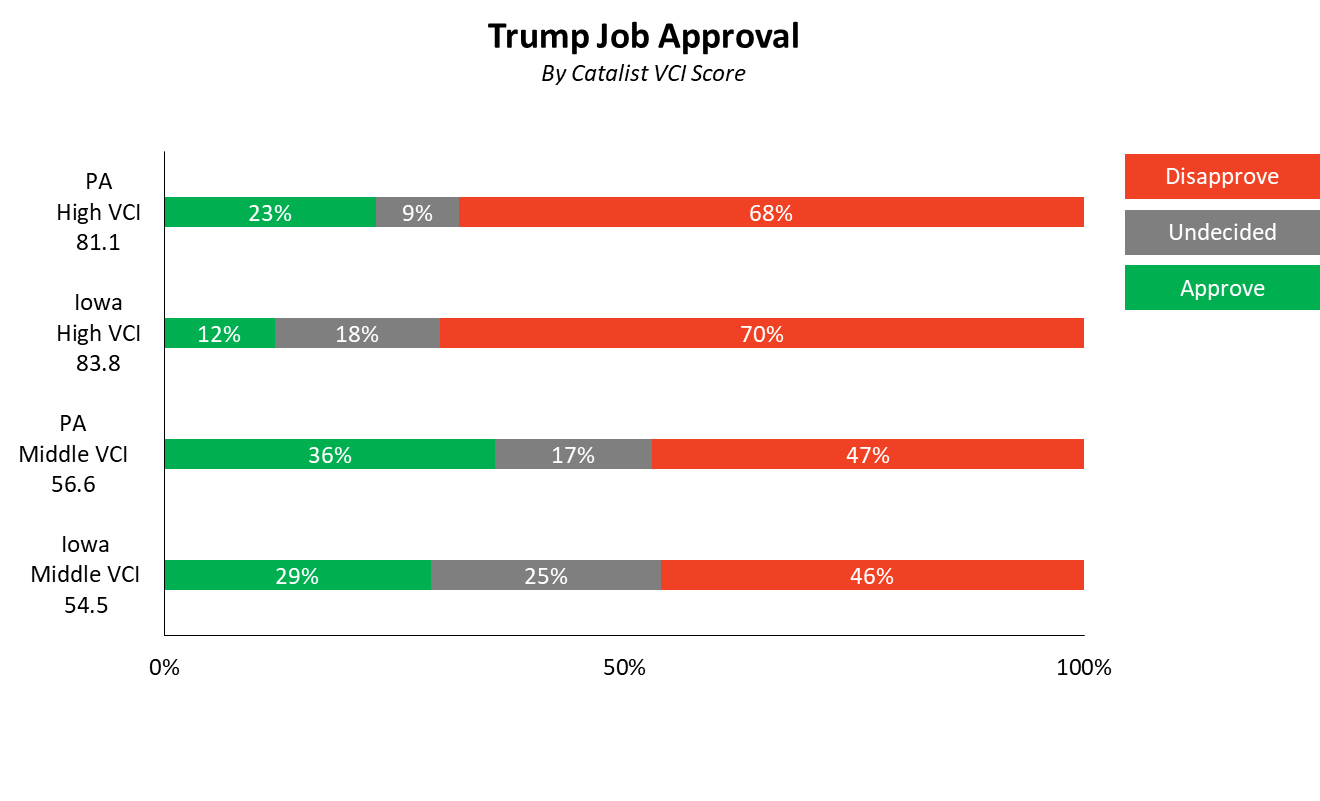

When we asked the job approval question of swing voters in working-class neighborhoods in the recent race in Pennsylvania’s 18th Congressional District, they had similar answers. But one segment diverged. While disapproval rates are roughly the same across the two states, Iowans are both more likely to be undecided about Trump and less likely to approve of the job he’s done in office than voters in PA CD-18.

Among likely Democratic voters in PA CD-18, just 9 percent were undecided about Trump. Twice that many likely Democratic voters in Iowa were undecided about Trump. In Pennsylvania, 23 percent of high VCI voters approve of Trump, but roughly half as many high VCI voters in Iowa approve. Both measures indicate weak support for the president.

When it comes to swing voters, the differences are less pronounced, but they’re apparent nonetheless. We see an 8-point gap between swing voters in Pennsylvania and Iowa, with 17 and 25 percent of voters undecided, respectively. There’s a similar gap in terms of Trump approval. One in 3 swing voters (36 percent) in Pennsylvania approve of the president, compared to 29 percent of swing voters in Iowa.

These numbers indicate that Iowans aren’t as enthusiastic about Trump as Pennsylvanians are. Anecdotally, our canvassers spoke with lots of people who voted for Trump, but were concerned and underwhelmed by his time in office.

Barbara, 70, of Maquoketa, is a retiree who voted for Trump. She said, “We need change, something different. I was a Democrat for all of my life until last time, until I voted for this person who’s in there right now. How was I supposed to know what he would turn out to be?”

Tamara, 50, of Dyersville, said, “I literally don’t know the difference between Republicans and Democrats. I avoid politics, I don’t even understand it.” She said she voted for Trump but felt “misled.”

Our conversations indicate that regardless of their reason for pulling the lever for Trump, a segment of voters is not seeing the results they had hoped for and may have regrets.

Fed up with the status quo, moderate Iowans are tuned out of state politics, revealing weak support for Gov. Reynolds and Rep. Blum.

When thinking about Iowa, the image that comes to mind might be of the Iowa caucuses, with impassioned partisans flexing their outsize influence in presidential contests. Our conversations reveal a different picture. Our canvassers frequently spoke with Iowans who were frustrated by stagnation and tuned out of state politics.

Brett, a 44-year-old Cedar Rapids resident, is an independent who voted for Clinton. Brett was candid about his lack of engagement with politics, saying, “I don’t watch the news or even read it unless there is something I want to know about.”

Similarly, Jade, a 37-year-old Dyersville resident, considers himself nonpartisan and voted for Clinton in 2016. When our canvasser asked where he got his information about politics, he said, “I don’t.” Elaborating on his 2016 vote choice, he said, “My wife and I went and we looked and we looked … eventually we went Democrat. I don’t know why. I’ve never voted that way in my life.”

Many of the people we spoke with said that while they may pay some attention to national politics, they didn’t track what was happening at the state or local level.

Lynn, 50, of Cedar Rapids, said, “I’m not gonna lie, I don’t really know much unless it’s the presidential election.”

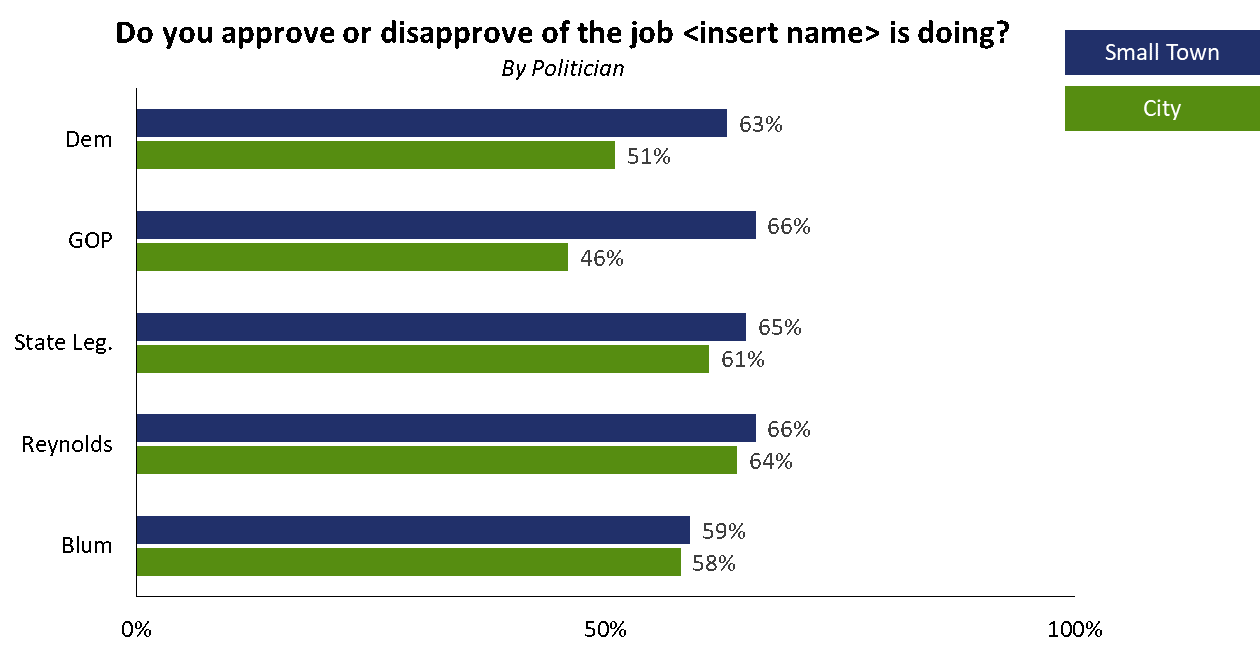

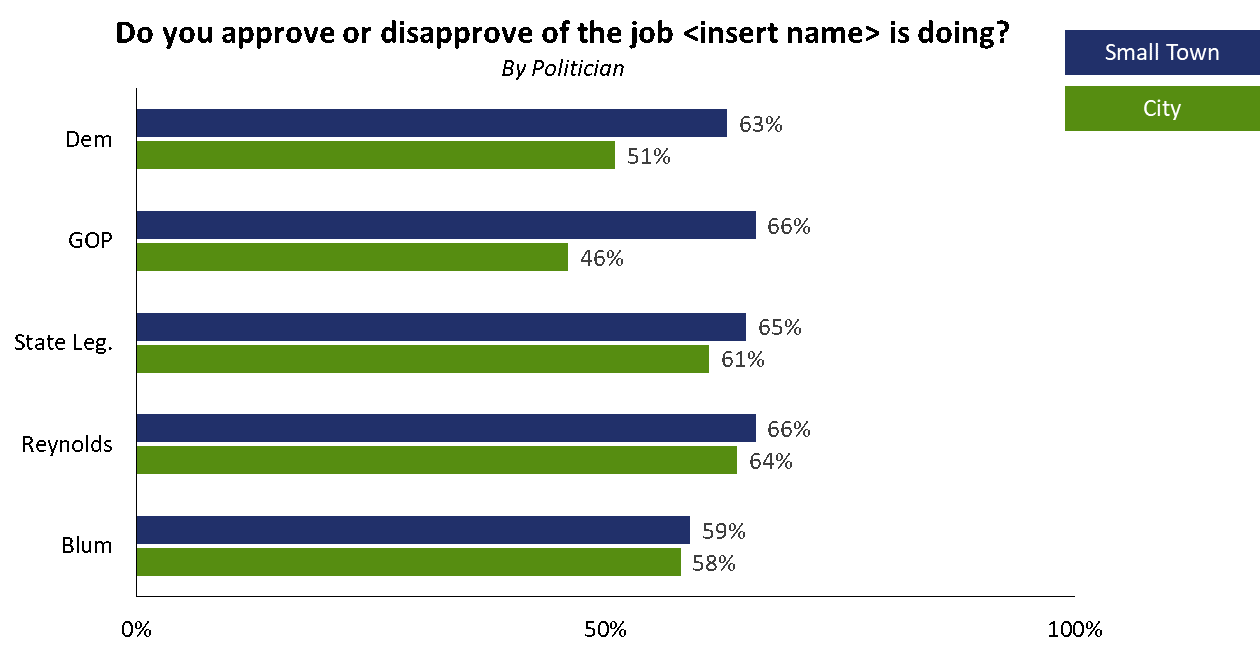

The data from our conversations supports this anecdotal evidence. When we asked people for their opinions on the state political parties, Gov. Reynolds or Rep. Blum, sizeable majorities of voters said they had no opinion. The chart below shows the percentages of people expressing no opinion about the state parties or elected officials, divided by cities (Cedar Rapids, Dubuque and Waterloo), and small towns (Dyersville, Maquoketa, and Oelwein).

Residents in small towns were more likely to have no opinion of state parties or elected officials. But regardless of whether someone was a swing or likely Democratic voter, the rates of people expressing no opinion remained similar.

These numbers suggest that Iowans are generally disinterested and disengaged from state politics. While Reynolds has only been in office since May 2017, Blum has run for office three times. This suggests a widespread lack of awareness of Blum among his constituents and potentially spells trouble for him in the fall.

Budget cuts — and mental health cuts in particular — struck a nerve regardless of voters’ partisan leanings.

In 2015, then-Gov. Terry Branstad closed two of Iowa’s four state mental hospitals. Branstad argued that private companies could provide better care than the state hospitals. Branstad also oversaw privatization of the state’s Medicaid program in 2016. A 2017 Des Moines Register/Mediacom Iowa poll found that Iowans strongly disapproved of cuts and privatization. Nearly two-thirds disapproved of how state leaders were handling mental health issues, and more than half disapproved of how state leaders were handling Medicaid, education funding and taxes.

In our conversations with Iowans, we asked whether they were concerned about the mental hospital closures. We found strong, widespread concern about cuts to mental health funding and the Republicans’ management of the health care system, with many voters raising the issue before we even asked about it.

Many people our canvassers spoke with had a personal connection to someone with mental health issues.

Scott, 53, of Cedar Rapids, felt strongly about the closure of mental health facilities in Iowa. He said, “My wife has a handicapped sister. Her care went through the floor after that. I have no problem paying more in taxes to take care of them.”

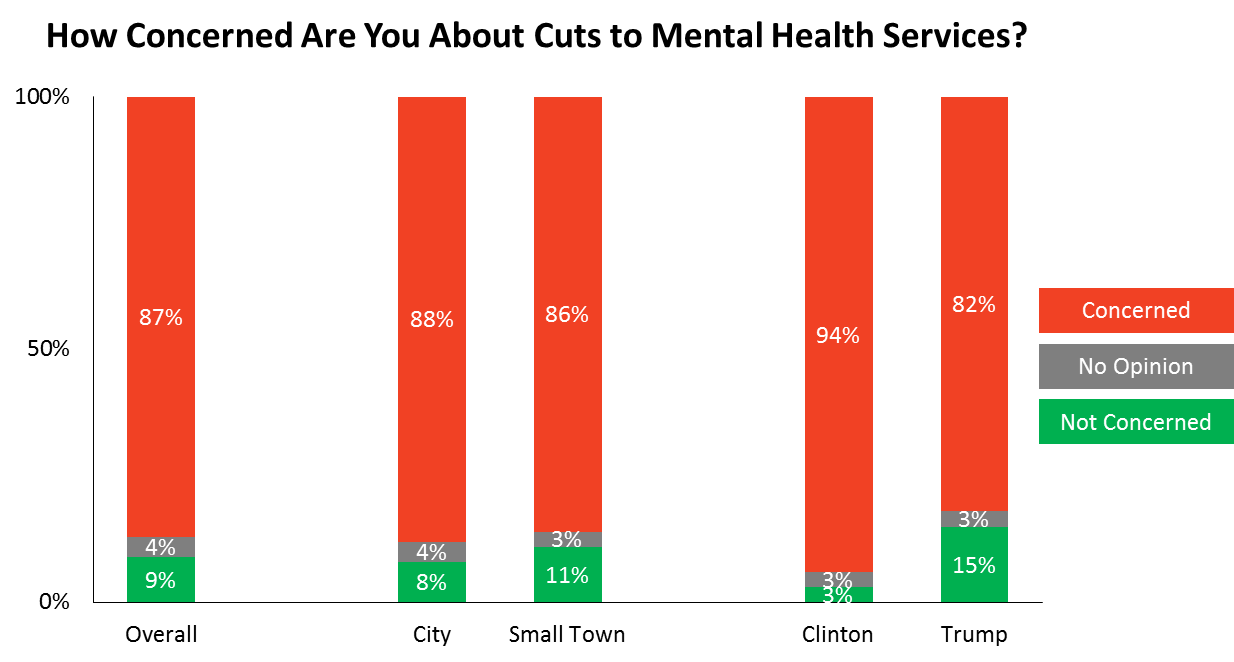

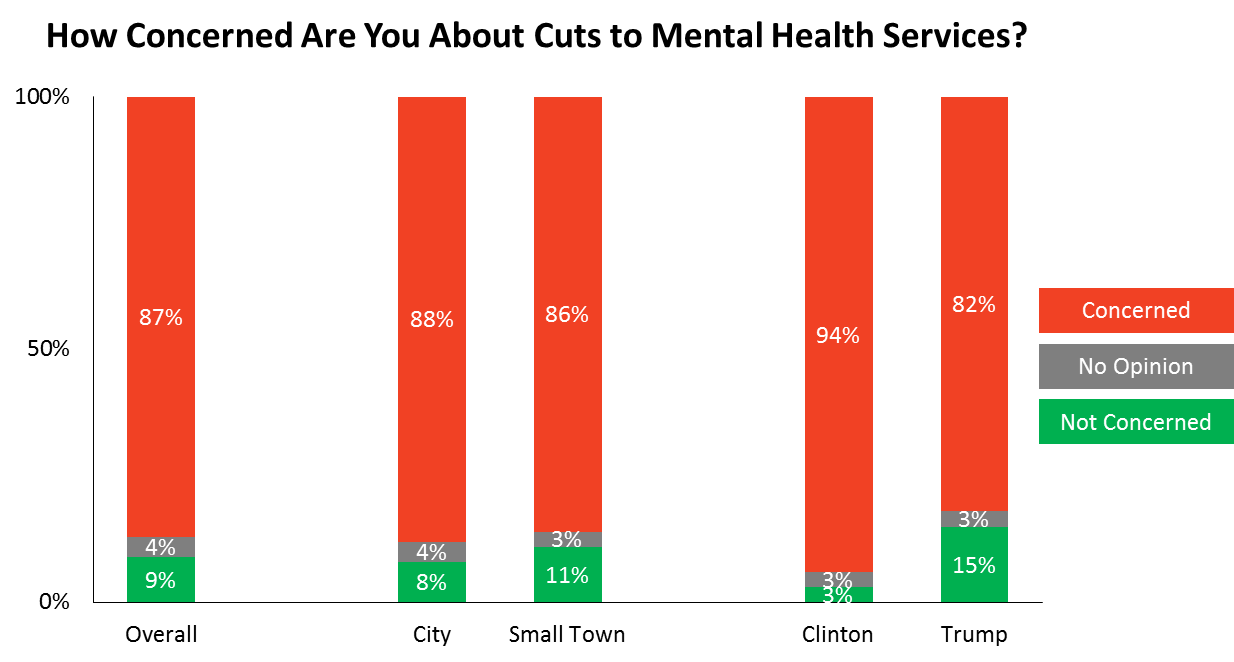

Even Trump voters disapproved of the mental hospital closures.

Kayla, a 24-year-old Cedar Rapids resident and Trump voter, said, “That was terrible. People aren’t serious about mental health. They like to put it down at the bottom like it’s no big deal. But if we actually take care of that problem first we wouldn’t have so many problems later.”

The numbers are striking — an overwhelming majority of Iowans are concerned about mental hospital closures.

Across all conversations, fully 87 percent of people were concerned about mental health cuts. While Clinton voters were more likely to be concerned than Trump voters, the numbers remain similar across different subgroups.

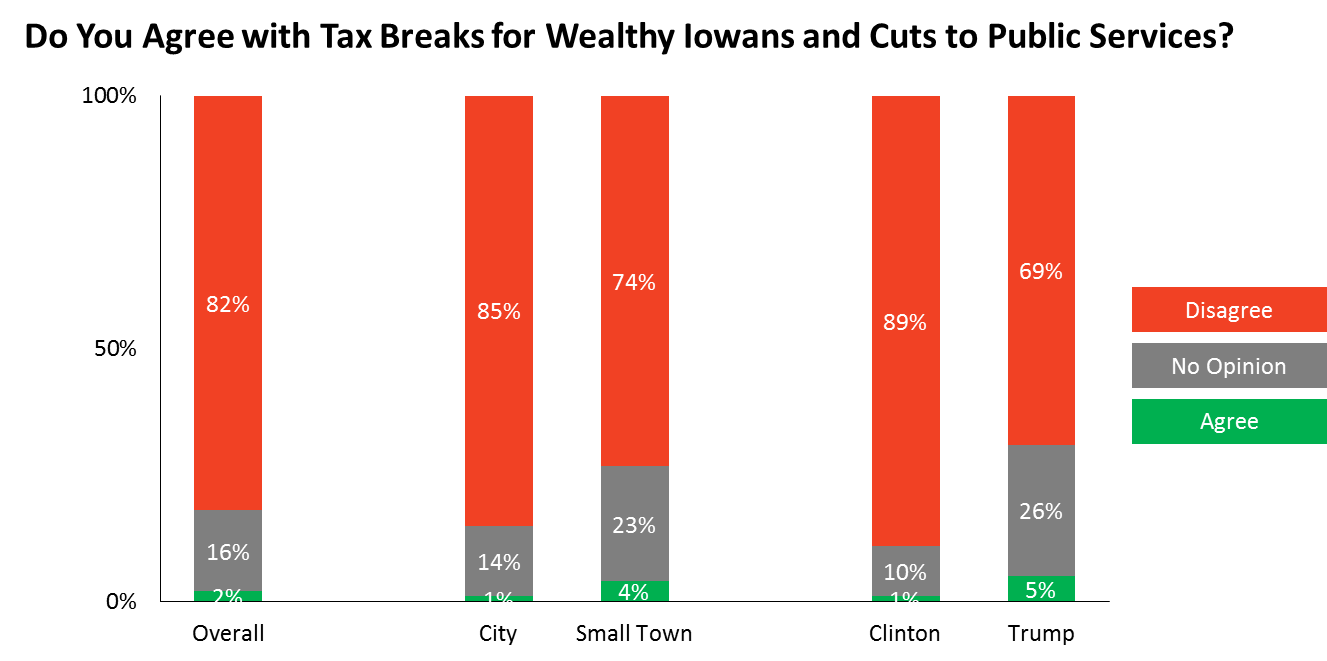

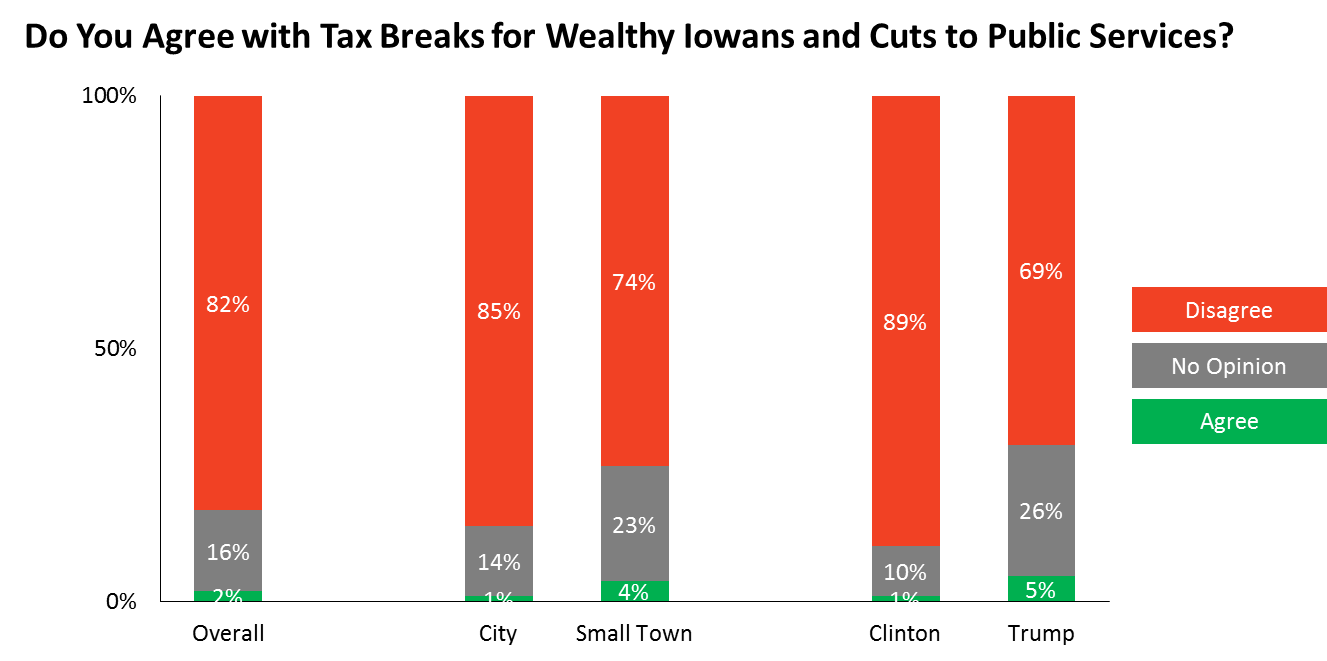

Iowa has a projected state budget deficit of at least $35 million in 2018. By law, legislators have to balance the budget. Reynolds and the state Legislature want to balance the budget by slashing funding for public education and human services, but they’re also proposing large tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy.

When we asked Iowans how they felt about Reynolds’ approach, they roundly disapproved.

Overall, 82 percent of the people we spoke with disapproved of Reynolds’ approach to balancing the budget. Here we see a significant gap between Clinton and Trump voters, with nearly 9 in 10 Clinton voters disapproving of budget cuts, compared to 7 in 10 Trump voters. Nevertheless, there is strong opposition to budget cuts regardless of how respondents voted in 2016.

The gulf between these low support numbers and actual policy proposals and bills advanced by state lawmakers suggests that voters lack an effective vehicle to make their collective voices heard. These numbers indicate that mental health and budget cuts could be a problem for Republicans in the fall.

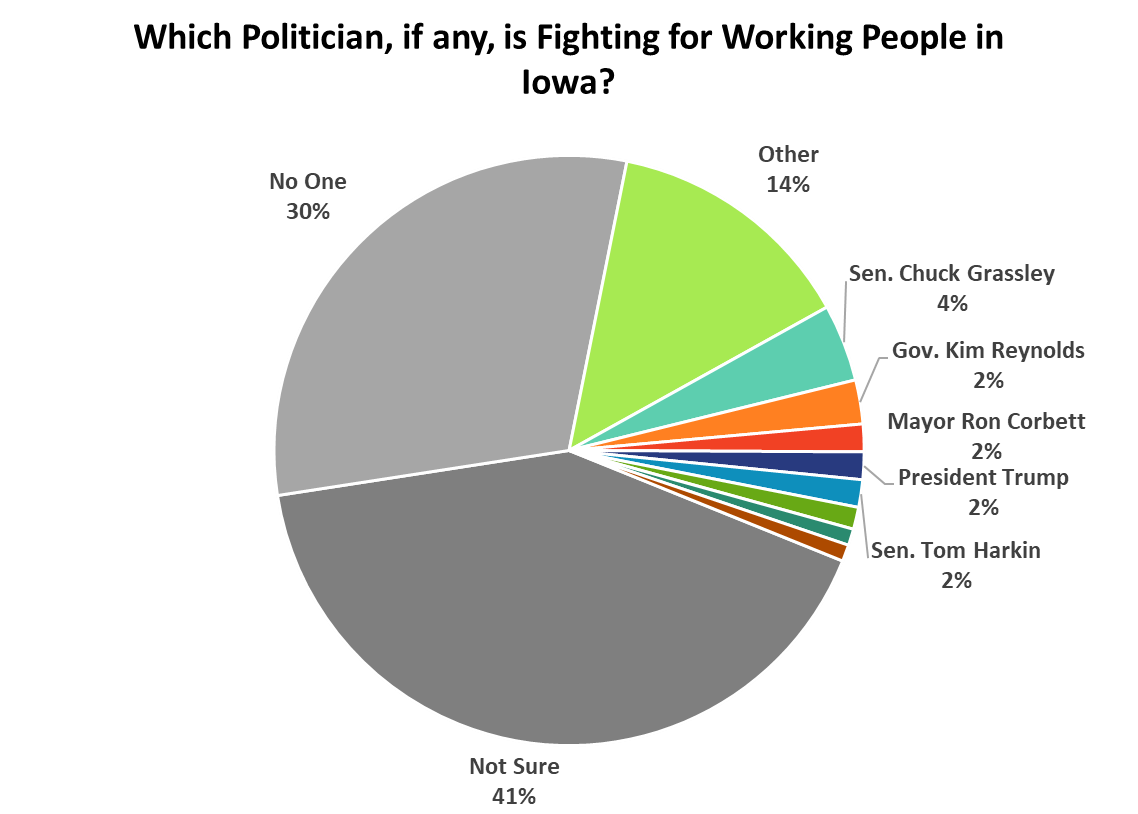

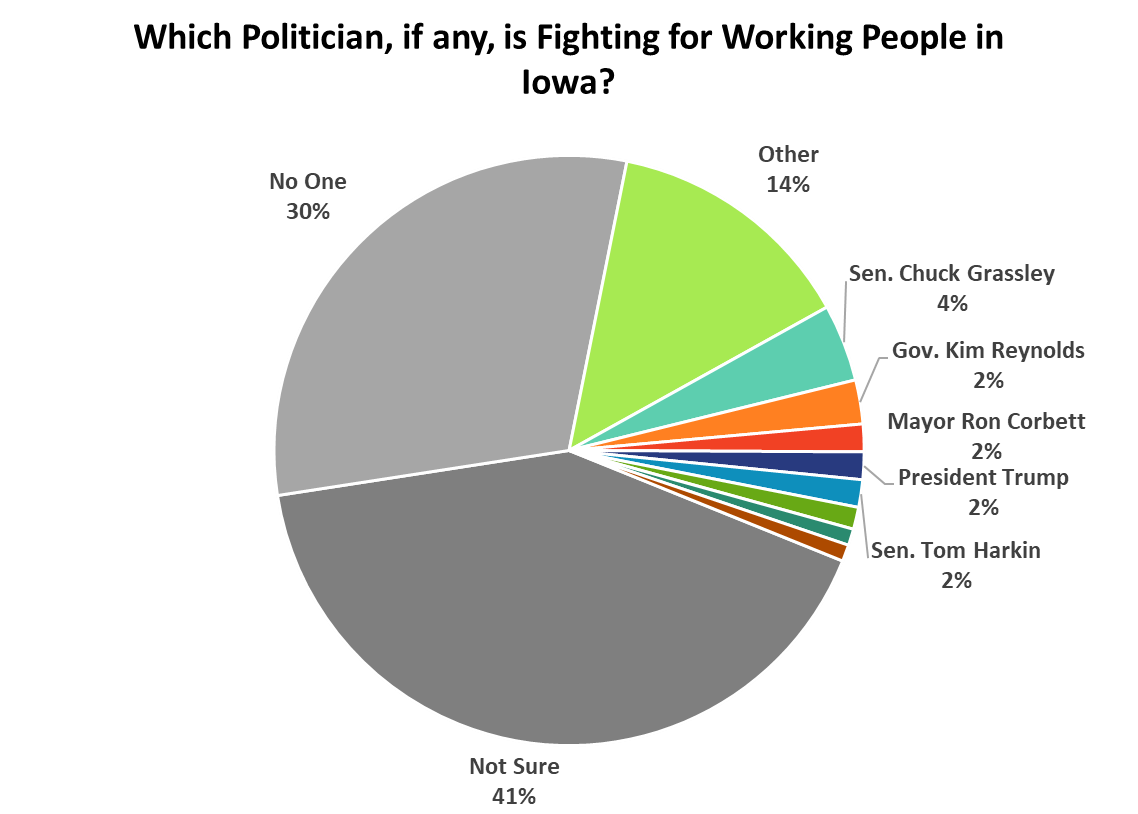

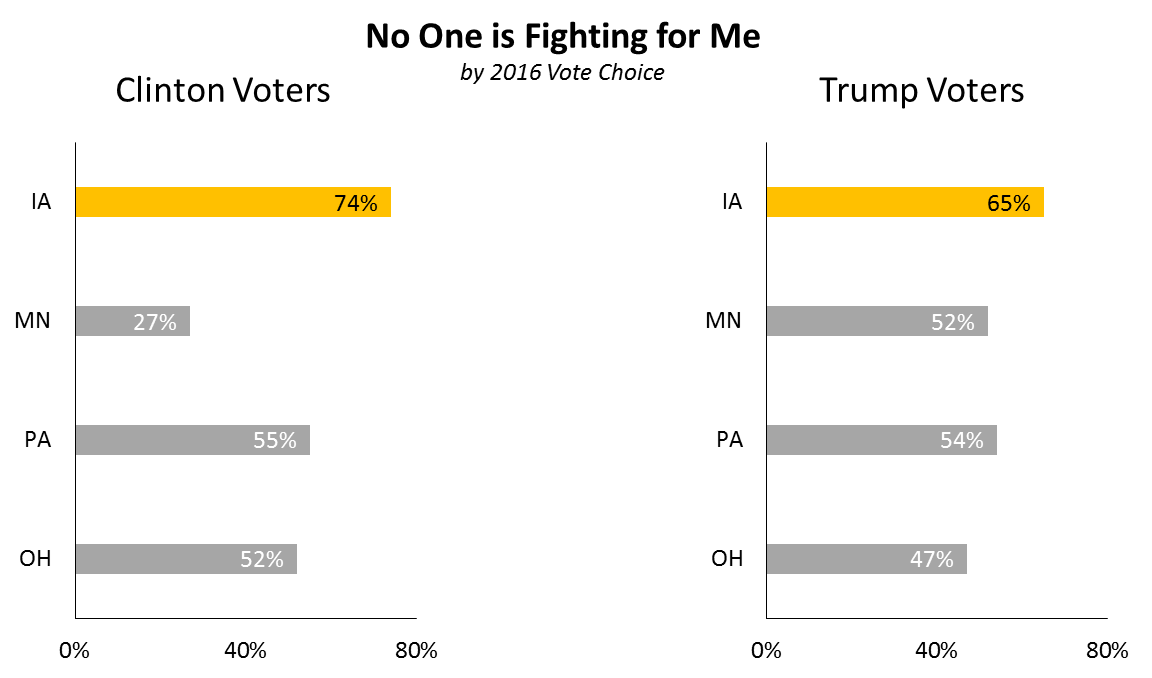

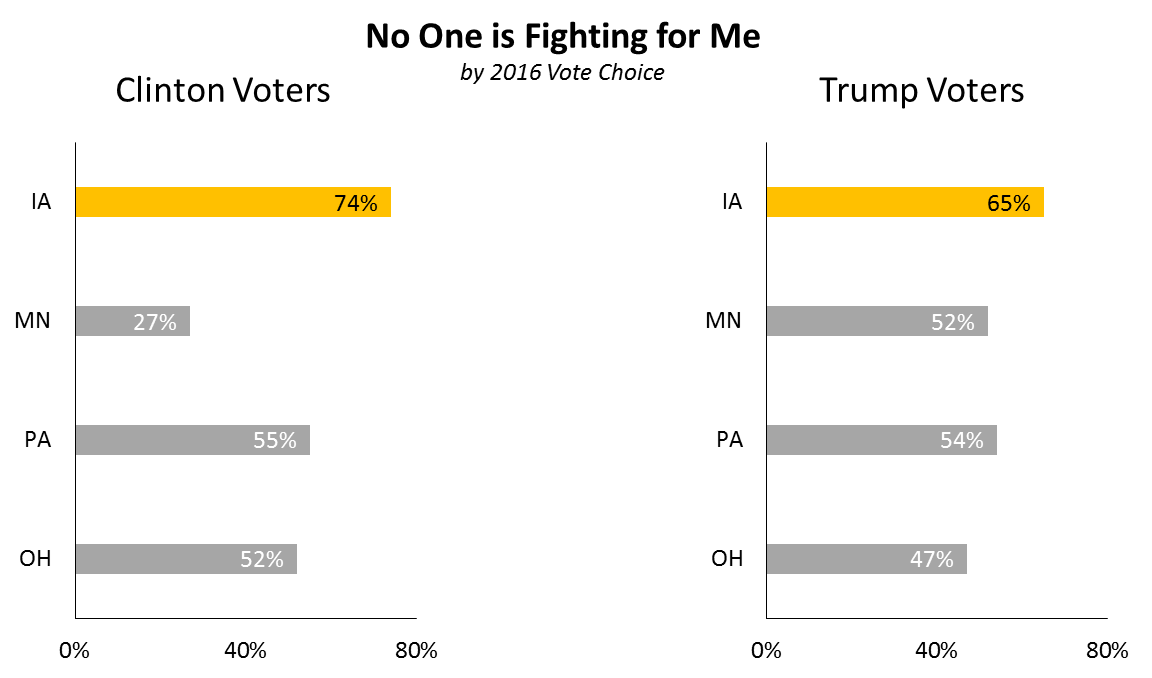

Of the people we spoke with, 71 percent said no politician is fighting for them.

We asked people if there was a politician they saw as fighting for them and their interests, and 71 percent of people couldn’t name such a politician. Of this group, 30 percent responded that “no one” in politics was fighting for them and 41 percent said they were unsure.

Charles, 71, of Maquoketa, paused for a while before identifying former Sen. Tom Harkin as a politician who fought for him. But he shook his head and said, “It’s been a long time since we had someone stand up for the working people.”

Compared to our work in other battleground states, Iowans are more likely to say that there isn’t a politician fighting for them or their interests.

The chart below breaks down responses to this question by 2016 vote choice and state. As with economic confidence, Iowa stands out from Minnesota, Ohio and Pennsylvania.

While this question doesn’t capture if there are groups or institutions that voters see as fighting for them, the fact that nearly three-quarters of Iowans we talked with don’t think there’s a politician fighting for them is another indicator of broad disaffection in the electorate. That said, we did find some voters who knew their local legislators. In Dubuque, Paige, 24, an IT professional concerned about access to healthcare, shared that she viewed Abby Finkenauer as a working-class champion.

Conclusion

Our front-porch conversations with working-class Iowans in and around Cedar Rapids reveal a complex picture on the ground in Iowa, with pitfalls and opportunities for Democrats in the upcoming election. The liberal and swing voters we spoke with were generally pessimistic about the economic future of their communities, fed up with state politics and unable to name a politician they felt had their back. On the issues, however, Iowans support good jobs, affordable health care, well-funded mental health services and quality public education. Whether it’s mental health or the state budget, Iowans support a greater investment in critical public services and were frustrated by the callous treatment of neighbors with mental health challenges. Given the overwhelming disapproval of mental hospital closures and budget cuts, progressives would do well to tie these issues to incumbent Republicans.

The lack of interest in politics and the resulting low information among Iowa swing voters presents an opening for progressives. In other states, we’ve encountered voters parroting Fox News talking points about the issues of the day. In Iowa, voters were largely tuned out. Rather than being inundated with right-wing messaging, many of the Iowans we spoke with were avoiding news altogether. Yet, they were hungry to engage and hold an authentic back-and-forth conversation with our canvassers about the future of their communities. While we found that a substantial segment of Trump voters was wavering in or questioning their support for the president, we can’t assume these people will show up to vote against the right-wing agenda in November without good information from a trusted source.

Methodology

Unlike traditional public opinion polling, which is based on a random sample of people representative of a given population, we targeted swing and likely Democratic voters in eastern Iowa.

From March 26 to April 10, Working America canvassed 335 registered voters.

In terms of demographics, the canvassed population skewed female (56 percent). A plurality of the canvassed population were millennials (42 percent) and most were not college educated (90 percent).

We canvassed in the cities of Cedar Rapids, Dubuque and Waterloo, as well as the small towns of Dyersville, Maquoketa, and Oelwein.

To get a more precise indicator of the partisan leanings of voters, we used the Catalist Vote Choice Index [VCI] score, which assigns a value of 0-100 to each voter, with higher scores signaling Democratic support and lower scores signaling GOP support. In order to reach swing and likely Democratic voters, we only spoke with voters with a VCI score of 30 or above.

We use cookies and other tracking technologies on our website. Examples of uses are to enable to improve your browsing experience on our website and show you content that is relevant to you.